Le CYCLE Masculin aude du Pasquier Grall

THE WORDS AND THE THING ABOUT AUDE DU PASQUIER GRALL’S MALE CYCLE

Evence Verdier

Texte édité dans Magasine et Centre d’Art virtuel « Synesthésie n° 12 - Contemporaines ». 2002.

Inaugurated in 1998, the Male Cycle now consists of four cycles numbered from one to four. A fifth cycle is currently under study. This multiform work unravels over the years and its ending has not been scheduled yet.

To each male cycle corresponds a different man and a different end result.

The Protocol

Aude du Pasquier Grall chooses her models among young heterosexual men. They are all rather shy and have no particular penchant for exhibitionism. They are on no account professional actors. She turns down those who may suggest a performance of some kind or those who could take advantage of their meeting to flatter their own narcissicism. They have to readily understand that this is an artistic experiment.

To each identity corresponds a particular cycle.

According to her protocol, the female artist asks her model to pose naked in her studio and to get an erection (without resorting to masturbation and without ejaculation) in front of her camera and/or her movie-camera.

Her tools define a geographical frontier for each of them: he is “on stage” exposed in front of the camera and instructed to stay there; she is on the other side, out of the visual field.

In this erotic encounter, they can only touch each other with their eyes and their words.

The work of a woman who likes men

The Male Cycle was prompted by curiosity and by a fascination for the transformation of the male sexual organs.

It turns out that the singular nature of each experiment, however strictly controlled, ruins the fantasized notion of a mechanical reaction from one cycle to another. The artist thus questions the great female mystery and claims that: “Man is the greatest mystery!” Or rather, men. It is certainly to pay homage to men’s complex nature and plural behavior that the Male Cycle has become a work in progress, multiplying hypotheses, and an elliptic work too, defined by the unknown, by want and double-entendre.

The richness of the exchange between the artist and her model conditions the variety of the production. The actor of Cycle n°4, who could not “get a hard-on on demand,” is thus paid an artistic homage, the diversity of which being at least proportionate to his own sensitivity and generosity.

The balance of power

Aude du Pasquier Grall demands specific poses and attitudes, a “formal” adaptation of her model, whom she precisely tries to “model” with her speech, so as to make him have an erection. To this end, he, in turn, sometimes asks for her “eroticizing” collaboration (“pull up your skirt,” “open your legs,” “show me your sex”…). The words are never vulgar. She writes: “If he cannot have an erection, I insist. I’m the one giving orders.” But then she adds: “If the man gets angry or tired, or worried, or if he has desires then he gives orders.” She gives him whatever he wants, within the tight frame of the protocol, minutely defined with distant reciprocity in mind.

This relation cannot be reduced to the sterile inversion of the classic tenets of machismo. It is not so much a question of the negation of power as a reflection upon the communicative use of power. The artist manages to create a relation based upon equality rather than upon the subordination of her model, and there are three reasons for this:

Firstly because her injunctions are confronted to the conditions established by the male model (“do something if you want me to get a hard-on”). Secondly, because a playful relationship is established between the two of them. One could even speak of complicity, which is obvious in cycles n°1 and n°4. In the first cycle, the model, shy at first, eventually appears more playful as he starts dancing in front of the camera as in Sam Taylor Wood’s Brontosaurus video. Thirdly, because the protocol is highly protective of their dignity. Potentially conflicting powers are neutralized by the accurateness of each in his or her part. Because the models that have so far been selected knew nothing about contemporary art, Aude du Pasquier Grall is able to underline their exceptional, intimate and intuitive grasp of the whole project, their intelligent apprehension of the situation.

A committed artist

The choice of title — “Male Cycle” — must have been suggested by humor or at least by the will to question our certainties about language. After all, the word “cycle” is associated with women. She uses “cycle” while others would rather use the word “mechanics,” bearing a physical rather than biological connotation. Is this a reaction to Louis Calaferte’s La Mécanique des femmes (translated into English as The Way it Works with Women)? In any case, this choice sounds somewhat less implacable, maybe even allowing room for a subject endowed with a capacity for variation within the cycle erection/slackening.

It even seems that the use of the word “cycle” is both improper and ironical. Man, as he is presented in the Cycles does not exactly correspond to society’s highly codified definition: potent and potentially filled with desire at the slightest stimulation.

“Cycle n°2,” contains rather pathetic moments, when the suggestions of the artist or the demands of the model who wants to get an erection fail to produce anything. Masculine frailty is suddenly exposed. Erection gives the model his self-assurance, as if it gave him a countenance and allowed him to be one of the “nudes in glory” described by Paul Ardenne in his book L’Image Corps (The Body Image).

The representation of man, fantasized as an eternal Priapus, erected at the very heart of a phallocratic society, is falling into pieces! No wonder the present work has been the object of censure: at the University of Toulouse Le Mirail, the exhibition was cancelled at the last minute even though invitations had already been sent.

At the end of the day, this work is not so much about the scandalous representation of male desire by a woman as it is about the impossibility for our society to accept the subversion of its symbolic structures.

If Aude du Pasquier Grall has been involved in a real social commitment ever since her Self-Portrait as a Dick-Head (1997), it is because she is truly interested in the power of vision. This is the main issue at stake in her work. Her utopian leverage is presented as a political counter-power. This is why she chose ambiguity. She has been reproached with not being “sexual” enough, or with being too sexual… Formally unfit for categorization, her creations partake of a particular esthetics. They are neither feminist nor vulgar, neither erotic (they do not aim at stimulating the sexual instinct of the beholder) nor pornographic, neither obscene nor scatological… They destabilize auditory and visual categories, and they contribute to the questioning of our perceptual habits. They are voyeuristic only inasmuch as the spectator remains deaf and blind when confronted to the scenography, the staging, the rhythmic quality of the ellipses, but also when confronted to the voices or to the noise of the machines, always recorded directly.

Zoé Léonard, Pin Up #1 (Jennifer Miller dœs Marilyn Monrœ), 1995, cibachrome, 145 x 105 cm.

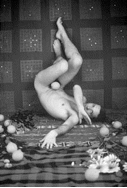

Aude du Pasquier Grall, Jeune homme à l’orange, (Le cycle masculin n°4), 2001, impression jet d’encre sur papier photographique, 175 x 120 cm.

Bronzino, Allégorie de Vénus, l’Amour et le Temps, milieu du 16ème siècle, bois, 146 x 116 cm.

On the art scene

Aude du Pasquier Grall is indeed provocative, but she is so in a very creative way. Her proposals are formally new even if, instructed by the history of art, they induce the mind to play with anachronistic alliances. One could, for instance, link a photograph taken from cycle n°4 (the man with an orange on his sex) to Bronzino’s painting Allegory of Venus, Love and Time. These two works both feature a well-balanced composition as well an artificial and foppish world, strange and sensual. The anti-naturalist bias, the improbable and contorted attitudes of the bodies, the mannerist colors, the intertwined themes of love, death and time, and even the representation of the golden apple — symbol of beauty — are echoed in both works. The leaf which traditionally hides the male sex (as much as it underlines it thanks to its suggestive shape) is here replaced by the round shape of an orange. The woman, who remains out of the photograph, is hereby signified by the representation of the male body. The model’s legs, flexed and joined together suggest an inverted deposition from the cross. Around him, flowers and fruits (oranges), normally the attributes of youth and fertility — on top of adding color to the composition! — are here carefully arranged on the ground so as to evoke a vanitas painting…

Other tracks may be explored, but the network of the history of shapes is clearly at works here and reminds us that nudes have not always been mostly feminine. Cycles n°1 and 4 renew with the figure of the ephebe, characterized by a slick and well-proportioned body, harmonious limbs and fine sinews. The representation of the model in Male Cycle n°1 is reminiscent of Caravaggio. His face even oddly resembles that of the Self-Portrait as Bacchus…

Beyond the corresponding sophisticated position of the bodies, the association of the Young Man with Oranges from Cycle n°4 and Zoé Léonard’s Pin Up #1 suggest a more precise definition of the issues at stake in Aude du Pasquier Grall’s research. Both artists work on the normative constraints of sexual attributes. Zoé Léonard questions their univocal distribution while Aude du Pasquier Grall questions their sexist distribution. In the video of Male Cycle n°4, she repeatedly asks her model to be “more masculine”, to avoid bending back, to smile in a “male” way! In Cycle n°3, the male model adamantly claims he has no breasts…

They both confront cultural icons. When Zoé Léonard takes photographs of her friend Jennifer, a bearded lady, in the provoking poses of Marilyn Monroe, she suggests we reexamine our cult images. When Aude du Pasquier Grall films her Male Cycle, she suggests we reexamine our representation of men and disturbs our imaginary. She gives men an opportunity to expose themselves in a different way, to appear fragile and each time different in their relation to sex. The gift is not his getting a hard-on but his accepting the staging of his challenged phallic power.

In Cycle n°4 (the video version), the model, apparently scandalously submissive, is paradoxically protecting his dignity because he exposes himself while playing with his own image. His zeal shows how conscious he is of parodying the animalized image of a woman “on all fours”.

According to Zoé Léonard, “women are over-represented as objects, but under-represented as producers. Likewise, the female sex is over-represented as an object for the eye, but under-represented as an experience”. Aude du Pasquier Grall is clearly an exception. In her Male Cycle, the female sex is not exposed but it nonetheless becomes the object of an experience. It is with the willing man, and not against him, that the artist has engaged in a reflection on the power of her work. The erected male organ is indeed the visual manifestation of a link established over the hours. The woman asks him to come down from his pedestal, but the man actually controls the gradual loss of his “aura”. And this is truly moving.

Evence Verdier fait partie de l'équipe rédactionnelle de la revue Art Press.

1 Male Cycle n°1 (1998) takes the form of a five-minute diaporama selected from a twelve-hour meeting between the artist and her model. Male Cycle n°2 (1999) is a sound piece lasting one minute and forty seconds and entitled The Prey. Male Cycle n°3 (2000) is a fifteen-minute video montage. Male Cycle n°4 (2001) came out under various forms: a twenty-six-minute video, The Thirteen Sessions; photographs (My Butterfly, Focalizing and the Miniatures series (composition with oranges and flowers) also offered as a diaporama); a seven-minute audio recording; scale 1:1 drawings that involve putting on paper all the details and contours of the artist’s and her model’s bodies; a video lasting four minutes and fifty seconds — Passion 1 — taken from a film showing the artist at work, recorded by a second camera…

2 Personal exhibition Male Cycle n°4, Contemporary Art Gallery, University of Toulouse le Mirail, February 4-15, 2002.

The Male Cycles, by Aude Du Pasquier Grall

Since 1988, I have been developing a series entitled “The Male Cycle”.

With almost scientific curiosity, I am shooting portraits of naked men according to a very precise process: I am always alone with them in my studio, with a camera or a movie-camera in hand, other cameras an microphones being positioned on tripods around the room. None of them is used to being naked in front of a camera. They are young and desirable, and they take an obvious social risk. Young and energetic executives, computer specialists, or medical doctors, they are not yet aware of the responsibilities of their future lives. Nonetheless, they offer their bodies to my eye and to my creative desire; they allow me to model them with words, like sculptures. The surprise, then the relationship that is created between us progressively determines the rhythm and shape of these “Male Cycles”.

Each one of these “Male Cycles” corresponds to one particular young man.

I try to represent masculine beauty and I show — with images and words — how it is generated. To me, the beauty of the male body is best expressed in a history of the cycles, on a period of time in which desire wavers.

We are in the painter’s studio but the artist is a woman. Based on an inversion of the traditional man-woman relation, it ironically disrupts the usual codes and stereotypes.

To create this sculpture of the self, to re-enact, subvert, reinvent the body and its words, confrontations and alliances arise between us. An ambiguous complicity is created: sometimes even a disconcerting submission.

This dual-voiced creation implies exchanges and alterations of our respective roles. We often play with great pleasure and humour, but, beyond beauty and desire, cruelty, exhaustion, emptiness and disappointment are a constant threat.

I question the relation between the female artist and her male models. The confrontation between men and women - with its symbolic constructions and relation of force - is for me an excuse to approach human issues. Then I continue my quest as male remains a great mystery to me.

In 2002, a personal exhibition: “Male Cycle n°4”, was censured in France. A certain number of institutions and media, together with the French Human Rights League have supported me to no avail. This video is also available in the collection of Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art of the Brooklyn Museum. Today censorship is still an issue in my work.

Aude du Pasquier Grall

***

***